We chat with Daniela Capuano, who is one of the first coffee roasters ever to receive an award from Un des Meilleurs Ouvriers de France recognizing craftspeople.

BY PAULO PEDROSO

SPECIAL TO BARISTA MAGAZINE ONLINE

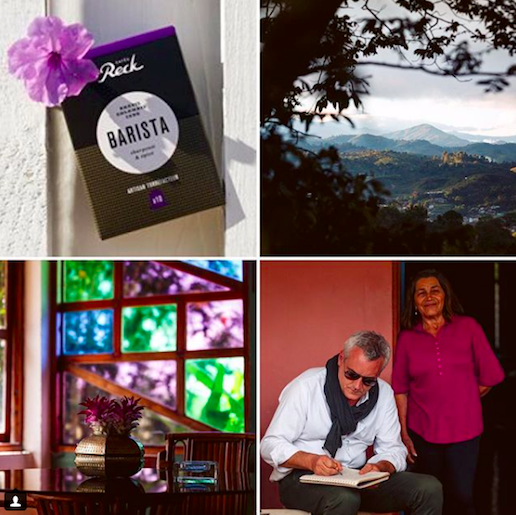

Cover photo courtesy of Daniela Capuano

Daniela Capuano is not only improving the quality of coffee in France, she’s conquering a country known for excellence and refinement in gastronomy. And to show that this recognition has no borders, she’s actually from Brazil.

For almost a century, the French National Education Ministry has recognized the excellence of craft workers through the Un des Meilleurs Ouvriers de France awards, also known as MOF. This year, for the first time, coffee roasters were honored as a competition category alongside chefs, confectioners, chocolate makers, and more than 200 other professionals. In this contest, the values and the professional skills of the competitors are recognized by their peers.

Achieving this lifelong title confers to the winning laureate a passport to an elite group of which the President of the French Republic is an honorary member. The award ceremony is followed, as tradition dictates, by a celebration at the Élysée Palace, the official presidential residence, in the presence of the current head of state, Emmanuel Macron. I talked with Daniela Capuano about winning the award, her background in roasting, and her journey through coffee in France.

Paulo Pedroso: What was your training and educational background in coffee roasting?

Daniela Capuano: My first contact with coffee roasting was in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, my homeland, around 2005, when I started working as a barista. I remember we used a Probatino 1kg coffee roaster. Then, I kept following the work of roasters whenever I could along my professional path. Even after moving to France in 2012 I returned to São Paulo, Brazil, one year later in order to join a profile roasting course with Isabela Raposeiras, from Coffee Lab, to go deeper on this process.

A few months later I went back to France and started roasting at L’arbre à Café, which had a 12kg Probat. It was founded by the French roaster Hippolyte Courty and I also worked there as a barista. Nevertheless, I took a new course by coffee expert Scott Rao in 2015, and today I am roasting on three types of Brambati equipment (120kg, 60kg, and 5kg). The courses have really helped me a lot, but I believe that the experience of roasting and the skill to reach a product of excellence is learned in large part through day-by-day practice.

The specialty-coffee movement is booming quickly in France, but it’s a recent phenomenon, isn’t it?

When I arrived in Paris in 2012, the specialty-coffee culture was just starting out, although there were some pioneers as La Cafeothèque, founded by a former ambassador of Guatemala in France, Gloria Montenegro. Coutume Café and Lomi Café had just opened their doors, and L’Arbre à Café ran only as a roasting brand for professional traders. But you could feel that things were warming up. Five years after that, this business reached a rapid growth, as well as the increasing of the knowledge searching by professionals and the consumers’ interest as well. Beyond Paris, where this growth is most visible, Bordeaux has also increased the supplying of fine coffee shops and roasters; other French cities are multiplying this movement like Nantes, Lille, Lyon, Marseille, and Strasbourg.

How do you evaluate the development of Brazilian beans and their presence in the global market share today?

Brazil is the largest world coffee producer, and our beans are usually found in the best blends around the world due to their sweetness and notes of caramel and citrus. The price of Brazilian coffee is also attractive when compared to other origins, and it can be advantageous for roasters, especially when they are an important part of their blends. Brazil has developed along the years the huge skill to produce high-quality beans and also customize a part of the production to specialty-coffee customers.

But, as a roaster and mainly as a Brazilian, I would love to see a faster development of terroirs coming from small batches like the great French wines. This Brazilian product is already around and reaching the high-end roasters, but in comparison with other countries on the top of the chain, our country still needs to increase its market share. At Café Reck, where I work today, Brazilian coffees represent our greatest volume. They are part of most of our blends, and customers love our single coffees based on beans from Bahia and Espirito Santo, which are the best sellers in our store.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Paulo Pedroso is a Brazilian entrepreneur who is a regular contributor to several newspapers and magazines. He always keeps an eye on the increasing reach of specialty-coffee culture and the trends and life stories that emerge from this phenomenon.